100 Hectares of Understanding

by Nela Eggenberger for EIKON Magazine

“‘Home’ is where you can say anything and no-one listens,” is just one of the innumerable examples of folk-wisdom on the theme of “family.” No wonder such an ambivalent terrain has been demarcated artistically in photography too. Indeed, since the 1970s such protagonists as Larry Clark, Nan Goldin or—later, in the 1990s—Richard Billingham have investigated their subcultural surroundings in an apparently amateur manner, which can scarcely be outdone for brutality or, at least directness.1 Tina Barney, on the other hand, lets her associates, rooted in the American elite, appear in fact in a better light, but an apparently impenetrable distance from her counterparts coupled with a tangible claim to be representative in her models also gives these portrait subjects something profoundly strange.2 In either case, photographic research into individual origins and the foundations of the self within one’s own family construct is always like walking a tightrope, where it is constantly a matter of the artist’s sensitivity as to whether they slip into distasteful sentimentality.

Jaakko Kahilaniemi (b. 1989 in Toijala) is also no stranger to this highly sensitive field. In his project 100 Hectares of Understanding (since 2015), as a person who has inherited a forested area north of the town of Tampere and consequently has to deal with the associated expectations of his family members, he establishes many connections with his own private background. In contrast, to the protagonists mentioned at the start of this essay, Kahilaniemi proceeds much more subtly in managing the problems: Due to his strictly conceptual procedure, his choice of minimalist aesthetics and especially the abstraction of the theme, where, for example, he denies himself the insertion of family portraits almost completely so that topical reference to private matters is only made through the work titles, he shifts the themes, in themselves always emotionally loaded, to a totally neutral, abstract level; at the same time he tries in this way “to grasp the significance of the 100 hectares of forest he owns.”

In addition, in 100 Hectares of Understanding there are crossreferences to general social rituals as well as Finnish clich.s. The former can be sympathetically comprehended by taking a diptych as an example: in Measured and Weighed (2015) a hundred seedlings are arranged in ranks and rows of ten time ten and reproduced photographically. They are matched on the other side with the sizes and weights of each seedling in the same arrangement. In its totality, Kahilaniemis analysis reminds one of a systematic photo album, where a young family documents its children’s first years of life—although the little plants, with their sterile mass repetition, are more like an educational wall chart than a baby-book filled with well-meant kitsch. In Property Weight (2016) it is again a matter of checking and weighing up, but in this case the title of the work is more definitely concerned with Kahilaniemi’s personal sensitivity.Here the reference to the heaviness of his land reveals the ambivalent feeling that for him goes along with his property; after all, in Finland, where wood is still seen as the most important raw material and as a result every fifth local family owns some area of forest, turning away from the forest industries, as in Jaakko Kahilaniemi’s case, is not a recipe for understanding.

For this reason it should not be a surprise that the themes of forests, nature and their cultivation represent a very significant part of classical Finnish folk culture and make their impact there by means of an imaginary ideal condition. Kahilaniemi is naturally critical of any such glorification and deals, for example, in Romanticism and Patriotism Studies (Gallen-Kallela, 1896) of 2017, with the nationalistic-romantic tendencies of the Finnish painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela, by blending the latter’s landscape painting, drenched in bright red, Skaters near the Shore of Kallela, with a photograph of his own forest, so that the ensemble comes to us in part as if seen through pink-colored lenses. Or he hints at this problem area in My Book of Our Land (2016), which refers to Sakari Topelius’s book Maamme Kirja (our land)—a patriotic text from 1875 originally written in Swedish, which was used in classrooms for several generations. In the case of this object-work, Kahilaniemi quite literally offers resistance by having a miniature fir tree sprout from the golden book cover. By drilling a hole into this stereotypical landscape turned book, Kahilaniemi emphasizes yet again that as an artist socialized in Finland through the idealization of the forest one can also see things in a very different way.

100 Hectares of Understanding

by Miha Colner

Contemporary art is often grave and serious, inspired by grand socio-political themes and phenomena. Commonly, it reflects on relevant issues such as political upheavals and injustice in society, it exposes absurdities of social norms and draws attention to (always too) short historical memory. And, of course, in the century of the self and within the self-centred mainstream culture many artists tend to externalise their own intimacy, identities and positions within society. Intimacy, sex, violence and fear always sell in politics, mass media, show business or art. In the visual arts, therefore, it is rare to come across seemingly marginal and insignificant narratives that focus on one’s personal experience of being confronted by life-changing situations, be it ruptures in daily routine, break-ups and breaks, births and deaths, love and hate, or even changing one’s profession and lifestyle. The artistic experiment of Finnish photographer Jaakko Kahilaniemi is a good example of the latter. It might be nothing new and nothing special; however, his way of dealing with his own situation by using exclusively visual means is extraordinary. It is visually appealing, conceptually challenging, cerebrally demanding, and thus utterly effective in delivering the impulses that might engage the audience. So, a couple of years ago, Kahilaniemi was caught off guard by the fact that he inherited quite a sizeable piece of land, a family property in the vast wooded territories of Finland. He was faced with a challenge of radically changing his old life in the city and – at least partially – move to the countryside to work on the land. Among a number of practical things he had to learn regarding farming, foresting, and maintaining the property he also needed to find a way to appreciate the might of nature and its unstoppable forces.

In the past several decades urbanisation and modernisation of life was immense in Finland and globally. Dealing with everyday life in the countryside might have been pathetic and pretentious a couple of decades ago, however, nowadays, in new circumstances, it is normal and legitimate. Society, including the artist himself, has slowly but surely been losing touch with the rural, traditional and static way of life. Despite (or because of) his lack of knowledge about forests and forestry, farms and farming, Kahilaniemi became analytical in his approach as he started observing and noticing things that hadn’t draw his attention before. For instance, he measured his land in a way that is not very meaningful to anyone but himself. In a way, his life-changing decisions and resulting actions seem to be romantic and almost spiritual, especially from the perspective of a contrasting clinical and generic urban lifestyle.

But there is a glitch. As much as foresting and farming may seem to be in tune with nature and its ongoing and inevitable processes, they are still alien and damaging – as any kind of regulation of the environment undoubtedly is. The inconvenient fact is that (we) human beings are pests of nature. Namely, farming and foresting can be as damaging for the environment as any kind of conventional heavy industry. Nowadays, when the world is collapsing into ecological catastrophe – overpopulation and mass production, which are constantly increasing, have brought our planet to the verge of ecological destruction. But humankind is still ignorant, despite the knowledge that it has become hostage to its own short-term economic interests that, proverbially, do not have an alternative. Kahilaniemi, in fact, has an alternative – an escape from the world of man-made structures, the cosiness of urban lifestyle and clichés of the art world. But is it really an escape? The artist’s decision to move to the countryside brings yet another soul into the wilderness thus claiming even more territory for invasive humans. However, he is aware of that problematic and does not claim he wants to save the planet; instead he is deeply fascinated by the forest, to the point that he started measuring it. He catalogued and exhibited branches, plants or cobs as if they were valuable archaeological artefacts.

What is strikingly unusual in these images is the specific photographic angle he uses which metaphorically reflects on people’s need to measure, inventory, systematise, archive, process and improve everything. Kahilaniemi actually demystifies the idea of living in rural areas. There is nothing romantic and nothing spectacular about it. Globalisation has hit the countryside hard but there is still something mysterious about it, something that still makes people think that nature has the power to put everything back in its place by itself and that there is some kind of a perfect order and balance that rules our lives and the lives of all living creatures on the planet. However, there is no such thing as perfect balance and perfect cycles in nature. It is only how we, human beings, imagine and impose our romanticised views on the nature.

100 Hectares of Understanding

by Helen Korpak

In Jaakko Kahilaniemi's Property Weight, one of the central pieces in the series 100 Hectares of Understanding, the viewer encounters a piece of wood on an old scale, like a newborn being weighed. Us humans do this all the time, consciously and subconsciously – we categorize, compartmentalize, analyze, organize. A baby is measured, weighed, scrutinzed for resemblance to parents, all within its first hours outside the womb. In an equally meticulous and loving way, Kahilaniemi approaches his most ungraspable possession – 100 hectares of Finnish forest. It's impossible to overstate the significance of forests for Finland, both historically and economically. 78% of the total area of the country is covered by forest – that's over 20 million hectares. With numbers like that it's hardly surprising that Finnish artists have always found themselves drawn to the forests. The late 19th century and early 20th century saw Finnish painters and photographers picturing landscapes dominated by forests and in more recent times, Antti Laitinen has represented Finland in the Venice biennale 2013 with deconstructed trees.

Kahilaniemi is also working with the method of deconstruction, but rather than creating physical work out of the results of this private ritual, he unveils the result through the medium of photography. Thus the dimension of time is added to his works – the viewer sees the fresh piece of bark or the green pine needles in Kahilaniemi's Picked Fragments #1-21, but knows that the moment is forever gone, as are the pictured fragments of nature.

In a way, Kahilaniemi is a contemporary incarnation of a land artist, a land artist of the rapid digital age in which the photograph has gained more value than ever before as a means of communication and information. Kahilaniemi captures nature through his lens before applying the alchemical process that makes art out of the familiar. This is in stark contrast to traditional land art, for which the photo is only a proof of existence that can never fully convey the experience of the actual site-specific work. Like Nils-Udo, whose work with delicate materials like flowers and leaves makes photography essential for capturing the result that may disappear within minutes, Kahilaniemi uses the documentary nature of photography to prove to himself and to the viewer that this very own 100 hectares out of Finland's 20 million does indeed exist.

100 Hectares of Understanding is also a work about shouldering the duties of adulthood. In works like Measured and Weighed or 100 Planted Saviors of the Heritage, Kahilaniemi tends to his forest, nursing it and taking responsibility for it. Hailing from a family of foresters, Kahilaniemi's own forest is both inheritance and heritage, a symbol of the artist's ancestry. It's also a very tangible origin: quite literally the roots of Kahilaniemi, who diverged from family tradition and became an artist. 100 Hectares of Understanding sees Kahilaniemi creating an intersection in which his own life as an artist meets the parallel life of Jaakko Kahilaniemi, the son of foresters.

Paternal expectations are a theme usually mulled over by older artists, often as a sort of cleansing ritual. Alejandro Jodorowsky was 86 when he made his autobiographical film Poesía Sin Fin, in which he deals with the difficulty of becoming an artist because of his father's disapproval, and Louise Bourgeois processed childhood memories until her death at age 98. It's rare for young artists to succesfully work with subjects like family history and parental relationships, but Kahilaniemi's 100 Hectares of Understanding is an eloquent meditation on these themes.

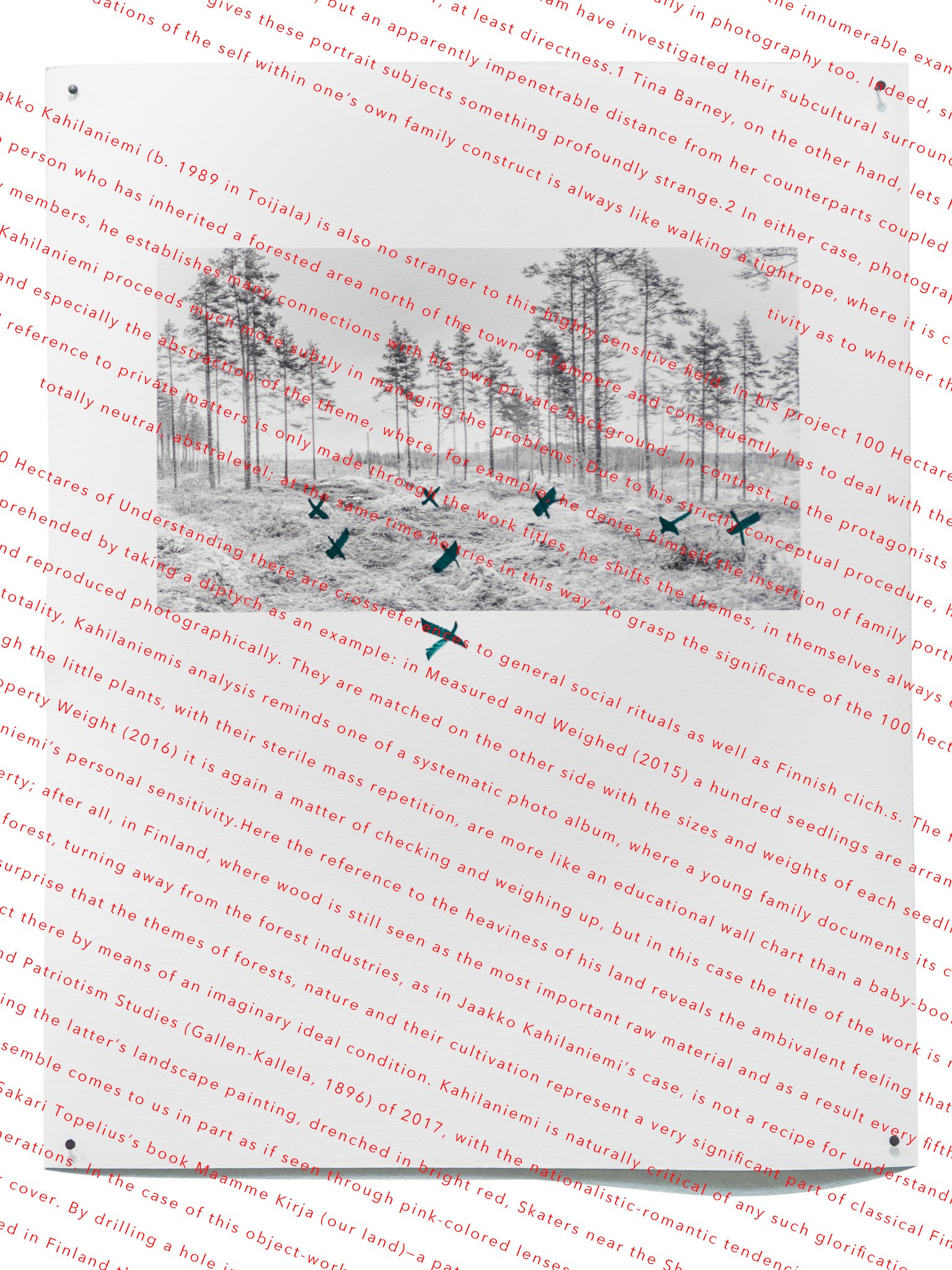

The meditativity becomes clearly visible in the documented acts which Kahilaniemi perform. In the collage of 18 photographs titled Hunting the Midpoint, the artist ploughs his way through ankle-deep snow into a typical young Finnish forest and out again. The act is simple, unpretenious. A similarly understated and evocative piece is Imaginary Borderline, in which cross sections of wood float upon a background of deepest black, not unlike the backgrounds of the achingly beautiful Dutch and Flemish 17th century still lifes. It's a secret map, as are many of the other works of the series. Kahilaniemi himself refers to some of his works as “visual secrets”, and in this lies the core of their strength: they are aesthetically beckoning yet enigmatic.